–More from Stiles and Teen Wolf

–More from Stiles and Teen Wolf

Art is like sex: when you’re doing it, nothing else matters.

“Go that way, really fast. If something gets in your way, turn.”

—Charles de Mar

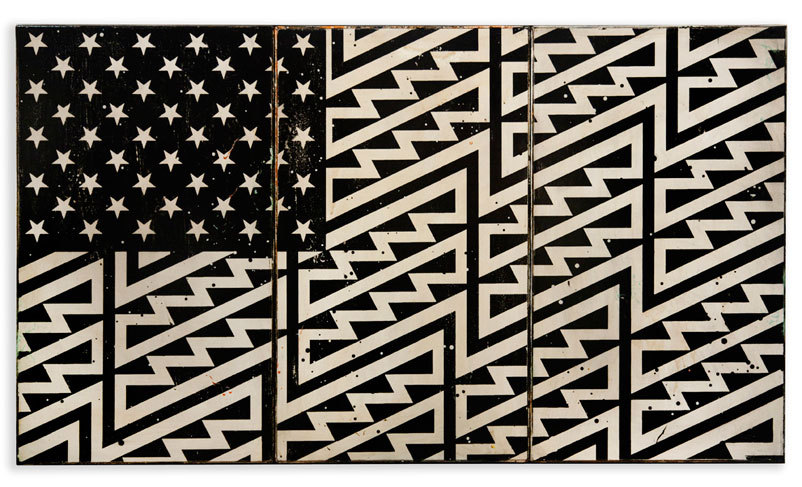

—Faile.

—Faile.

Via Gothamist.

“…we have not heard enough, if anything, about the female gaze. About the scorch of it, with the eyes staying in the head. ‘I love to gaze at a promising looking cock,’ writes Catherine Millet in her beautiful sex memoir, before going on to describe how she also loves to look at the ‘brownish crater’ of her asshole and the ‘crimson valley’ of her pussy, each opened wide—its color laid bare—for the fucking.”

—Maggie Nelson

“This pains me enormously. She presses me to say why; I can’t answer. Instead I say something about how clinical psychology forces everything we call love into the pathological or the delusional or the biologically explicable, that if what I was feeling wasn’t love then I am forced to admit that I don’t know what love is, or, more simply, that I loved a bad man….”

—Maggie Nelson

“…later that afternoon, a therapist will say to me, If he hadn’t lied to you, he would have been a different person than he is. She is trying to get me to see that although I thought I loved this man very completely for exactly who he was, I was in fact blind to the man he actually was, or is.”

—Maggie Nelson

Without even being conscious of it, I must have had various ideas about how a short story was “supposed to be.” I remember being at my desk, writing one story (later called “The Princess and the Plumber”), and in the story the plumber is getting love advice from a frog who is contemptuous of how the plumber is going about wooing a princess. I remember feeling this inner obligation to continue the dialogue between the plumber and the frog, even though I didn’t know what else they had to say to each other. Still, it felt like the conversation should continue on for at least another few paragraphs. Then I suddenly realized that there was nobody looking over my shoulder, and that nobody had any greater authority over what should happen next than I did, and the “me” to follow was the one who had run out of dialogue at that moment. That I should trust this “running out of dialogue” — not assume it was because I was stupid, but rather take it to mean that this part of the story was done. I wrote: “The plumber looked at the frog a moment longer, then turned and walked towards the bus shelter.” It was so freeing to have the plumber just walk away, and the rest of the story came swiftly — I just continued on following my impulses absolutely. It was the first time, writing, I had a sense for how total a writer’s freedom is. I don’t think that ever completely went away, and it seems the biggest leap I made: from thinking I had to write in a certain way to realizing that nobody was there with me as I was sitting at my desk — and for good reason — because your only obligation is to listen to yourself.

I think I saw you in an ice-cream parlor

drinking milk shakes cold and long

smiling and waving and looking so fine

don’t think you knew you were in this song

And it was cold and it rained so I felt like an actor

and I thought of Ma and I wanted to get back there

Your face, your race, the way that you talk

I kiss you

you’re beautiful

I want you to walk